Public art is a societal good. Studies show that there is a correlation between public art and safer streets, reduced mental stress on residents, and increased tourism. And while art is purely subjective, there are some pieces that almost universally make the viewer scratch their head.

In Cleveland, Ohio, that piece is the Free Stamp, which functions as the world’s largest rubber stamp.

Imagine, if you will, driving along Lake Erie, alternating your gaze between the midsized skyline in front of you and the water to your side. You pull off at East 9th Street and head into the heart of the city, crossing the freeway and turning away from the lake. At the first main intersection, there’s a one-block park to your right, where you see a big red… something. On a whim, you turn to the right and stop about 100 feet down the block.

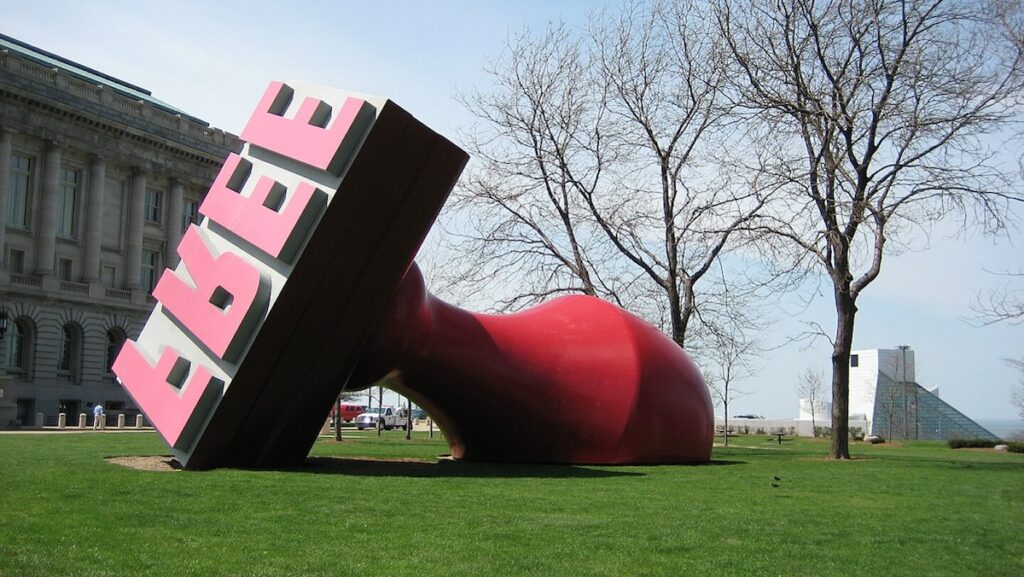

Congratulations, you have stumbled upon the Free Stamp, a 28 x 28 x 49-foot sculpture in the middle of Willard Park. It is, as the same suggests, a stamp. It appears on its side, as if someone tipped it over, which reveals the bottom – four giant letters reading “FREE,” but since it’s a stamp, the letter are backwards.

To say it’s a head-scratcher may be an understatement. Ask around to people who live in Cleveland and you’ll get a lot of shrugs. Some people hate it, some think it’s dumb but worth a laugh, and surely some think it’s a delight. But despite it being a relatively recent addition to the city (the late 1980s), it seems like almost nobody knows the story behind this iconic/bizarre landmark.

The Free Stamp’s Origins (Oil Companies, Man)

Standard Oil of Ohio, affectionately known as SOHIO, commissioned an artwork for its new Cleveland headquarters in 1982. SOHIO, which is a fascinating and very long story in its own right (It’s really the tale of John D. Rockefeller’s incomprehensible wealth and power; his Standard Oil company was broken up into 43 subsidiary companies which became Chevron, Exxon, Mobil, Marathon, and BP – the biggest oil companies in the world – among others. All of those came from one company.), was planning a skyscraper in Cleveland’s Public Square and wanted a centerpiece to complement the city’s Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument. That monument is in honor of the 9,000+ residents of the county who fought for the Union in the Civil War. With that in mind, when designing the artwork, the artists chose the word “FREE” as the text on the stamp.

However, in its original design, the stamp would be right-side up as if it were on an ink pad, so the word would be hidden from view. Even so, the designers (Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen) wanted it to be hidden and perhaps thought it would be a comment on freedom and liberty in these United States.

As construction got underway, SOHIO was under new management. These new people did not think a big, weird stamp should be outside their headquarters in the main square of the city of Cleveland, particularly as the city was in a bit of a decline. SOHIO’s new management said, “You gotta put this someplace else” and the artists said “nej” (Oldenburg was Swedish) and “nee” (van Bruggen was Dutch). Since everyone was being very mature, the next logical step was to stop production on the stamp for a handful of years as pieces were placed in storage in Indiana, for some reason.

But then, as they SO OFTEN do, a multi-billion-dollar company saved the day. BP assumed management of SOHIO. Someone checked their accounting books and realized they were paying thousands of dollars to store a giant stamp in a warehouse in Indiana. Not ideal. As a result, an olive branch was extended and the artists were invited back to choose a new location for the stamp, landing on Willard Park. Why Willard Park? Because it’s directly next to City Hall.

The president of Cleveland’s City Council was none too pleased with this particular form of artistic expression and talked a lot of trash about the artists and artwork. In fact, Oldenburg and van Bruggen threatened to destroy the work altogether if a resolution couldn’t be reached. But November of 1989 brought a new City Council President, and the work was finally going to find a home.

Redesigns were made when the new location was determined, as the artists decided that the stamp would look better lying on its side. This also allows the public to see the stamp’s text. Van Bruggen reportedly told an interviewer that the new design reflected the history of the artwork as it was “flung” from Public Square and landed in Willard Park.

BP formally donated the Free Stamp to the city of Cleveland and the company was able to remove it from Indiana and drop it smack in the middle of Willard Park, where it remains to this day.

The stamp was inaugurated on November 15, 1991. Frankly, I do not know what inaugurating a stamp can possibly mean, but it happened nonetheless.

Now why can’t a billion-dollar corporation swoop in to save the RoboCop statue in Detroit (and yes, I get the irony there)?