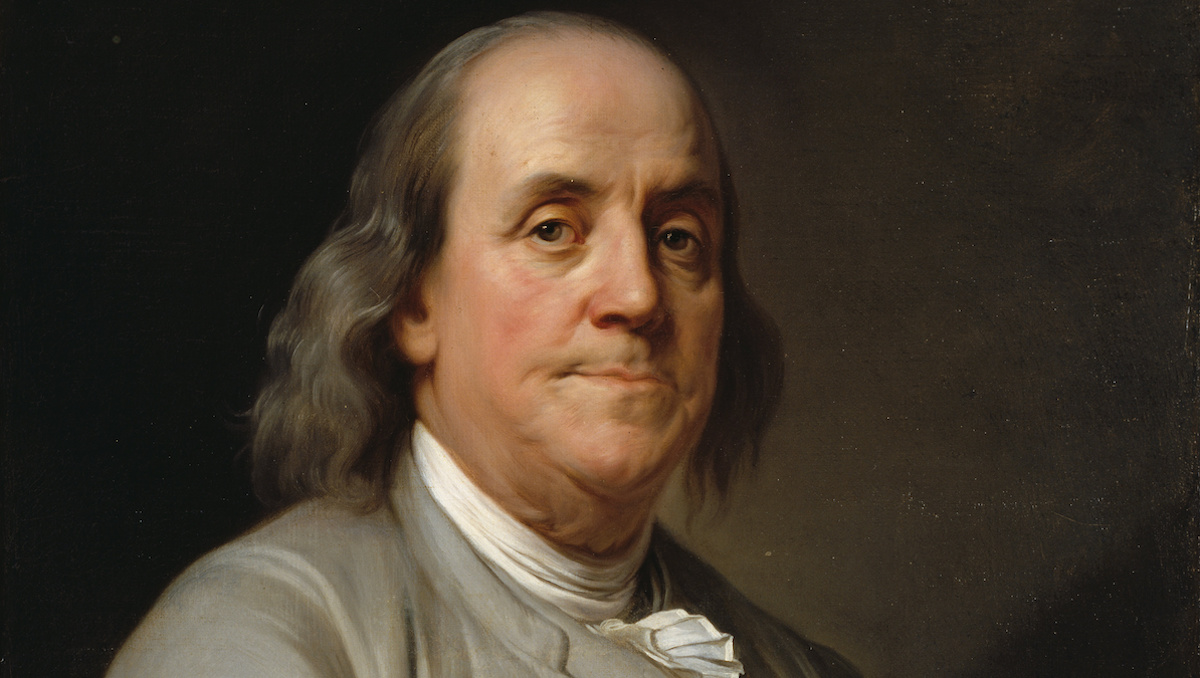

Benjamin Franklin may be the most famous Founding Father who was never a president. An incomplete list of things named after ol’ Ben include: 24 U.S. counties, two mountain ranges, seven colleges, dozens of schools – including one elementary school in Barcelona – bridges, a zoo, multiple Navy ships, and a crater on the moon.

And that’s to say nothing of his face being on the $100 bill and being the subject matter of one of the most mid-90s rap videos you could ever imagine. (youtube link to All About the Benjamins would go here but YT is blocked on my work computer)

Franklin wrote or received something like 30,000 letters or works in his life, including those regarding the American Revolution, the famous Poor Richard’s Almanack, and personal letters to his son William, who was on the wrong side of the Revolutionary War. The near-entirety of these works has been painstakingly curated into The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, a massive collaborative effort to preserve and protect every extant piece of Franklin’s writing.

Buried within these works is one essay you are likely unfamiliar with: Franklin’s letter that has become known simply as “Fart Proudly.”

Ben Franklin’s Essay on Farts (Seriously)

That’s right. One of the greatest and most influential minds in American history wrote an essay about farting. And it’s incredible.

The backdrop of this particular letter is that Royal Societies were a really big deal in the 17th-19th centuries. Perhaps the most prominent among these was in the U.K., where in 1660 the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge was formed. The Royal Society still exists, but with science being accessible to the masses, it’s not quite the same as it once was, and it once was the meeting place for the finest minds in the West.

At any rate, in about 1780, the Royal Academy of Brussels issued a call for scientific papers. Our hero, Ben Franklin, was tired of it. He felt like these academies and institutes were too pretentious and focused on big-picture philosophical ideas which would affect a handful of people instead of the population at large. As a result, he looked deep within himself and wondered if there might be a way to help the world on a personal, internal level.

Franklin posed one of life’s great questions: What if we could make farts smell good?

At a glance, this feels like a joke. And it probably is, considering Franklin didn’t actually send in this letter as an honest submission, but he raises some interesting points within the text.

For example:

“A few Stems of Asparagus eaten, shall give our Urine a disagreable Odour; and a Pill of Turpentine no bigger than a Pea, shall bestow on it the pleasing Smell of Violets. And why should it be thought more impossible in Nature, to find Means of making a Perfume of our Wind than of our Water?”

The guy does have a point. What’s more, Benny points out that it’s easy to make farts smell worse so doesn’t it stand to reason that we can make them smell better? “He that dines on stale Flesh, especially with much Addition of Onions, shall be able to afford a Stink that no Company can tolerate…” Two-hundred and forty years ago, our forefathers knew that onions and bad meat could clear a room. How have we not progressed?

But the star of the show here is the language. The amount of times Franklin uses phrases like “a great Quantity of Wind” or “permitting this Air to escape…” or “…the odiously offensive Smell accompanying such Escapes” is truly the vernacular of genius. He takes a delicate topic and delicately douses it in gasoline while holding a lighter. It is brilliant beyond reproach. It also leads us to wonder if Ben Franklin had particularly stinky gas. It’s rare to come across such potent sensory imagery.

What’s more, he goes to town on the notion of studying high-concept philosophy that won’t matter to nearly anyone. This one is so good that it’s a block quote:

Are there twenty Men in Europe at this Day, the happier, or even the easier, for any Knowledge they have pick’d out of Aristotle? What Comfort can the Vortices of Descartes give to a Man who has Whirlwinds in his Bowels! The Knowledge of Newton’s mutual Attraction of the Particles of Matter, can it afford Ease to him who is rack’d by their mutual Repulsion, and the cruel Distensions it occasions? The Pleasure arising to a few Philosophers, from seeing, a few Times in their Life, the Threads of Light untwisted, and separated by the Newtonian Prism into seven Colours, can it be compared with the Ease and Comfort every Man living might feel seven times a Day, by discharging freely the Wind from his Bowels?

It’s… masterful. The capitalization, the imagery, the acknowledgement that reading Newton is useless to 99.9% of people. He’s really got it all.

I won’t spoil the ending, but you should know that the final line is a delightful pun on a form of currency and is 100% worth your time to read.

In truth, Franklin didn’t send this letter to the Academy. He instead chose to send it to his friend, Richard Price, who happened to be a serious philosopher. That’s not quite the same as a submission, but it’s not like he just shared it with his best friend (though he did that too: Franklin reportedly printed copies and gave them out to his buddies, including a famous chemist named Joseph Priestley).

Lastly, take solace in this. One of the greatest minds our nation – and perhaps the world – has ever known was concerned about holding in farts. He knew, just as you know, that it’s uncomfortable. And oh, what glories our lives could enjoy, were we to release freely such Winds as those trapped with’n us. Breathe freely, great Winds. Go forth. As Franklin has writt’n.

Fart at will.