“I am vast, I contain multitudes,” goes one oft-quoted line from “Song of Myself” by Walt Whitman. In the American literary canon, the questions and ideas explored in Whitman’s poetry are taught as exploring humanity’s place in the universe; students learn to regard Whitman as philosophical and erudite.

But I am here to tell you, you can celebrate the Halloween season with the poetry and biography of “My W.W.” The morbid is absolutely contained within Whitman’s multitudes.

Walt Whitman vs. Edgar Allen Poe

In 1880, Whitman reviewed a new collection by Edgar Allen Poe in his diary. He was not a fan, ultimately concluding that the “nocturnal themes” in Poe’s work, as well as the pretty word choice and rhymes, may be “dazzling” but contain “no heat.” He thought these dark, lilting poems of Poe were a fad that would fade out.

Ouch.

Later in Whitman’s life, he felt less harshly about Poe’s work and style (New Jersey State Park Service, guided tour of Walt Whitman’s home, 10/8/23). A tour guide of his Camden home suggested that after Whitman’s long life, watching friends and loved ones die, as well as his experiences visiting with injured Union Army soldiers in makeshift Civil War field hospitals, Whitman grew more intimately aware of the realities of death. So of course, his poetry and other writings would reflect this.

When I visited Whitman’s historically preserved home in Camden, NJ, I couldn’t help but notice that every room was filled with jars of plastic lilac blooms, a nod to his memorial poem for President Lincoln, “When Lilacs in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” The plastic flowers were added to the reconstructed rooms in the decades since Whitman’s passing, but the image of the lilac in Whitman’s work has a morose significance. Lilac season is short – they bloom for just about two weeks – and all human life feels short in the end; these are some of the melancholy observations in this poem. Whitman’s elegy to the assassinated president, set in a “moody, tearful night,” feel just as harrowing as EAP’s “craving heart, for the lost flowers.”

I would argue that Whitman’s work has always had a creepier vibe than even he would have thought when he was writing it.

Walt Whitman’s Grave

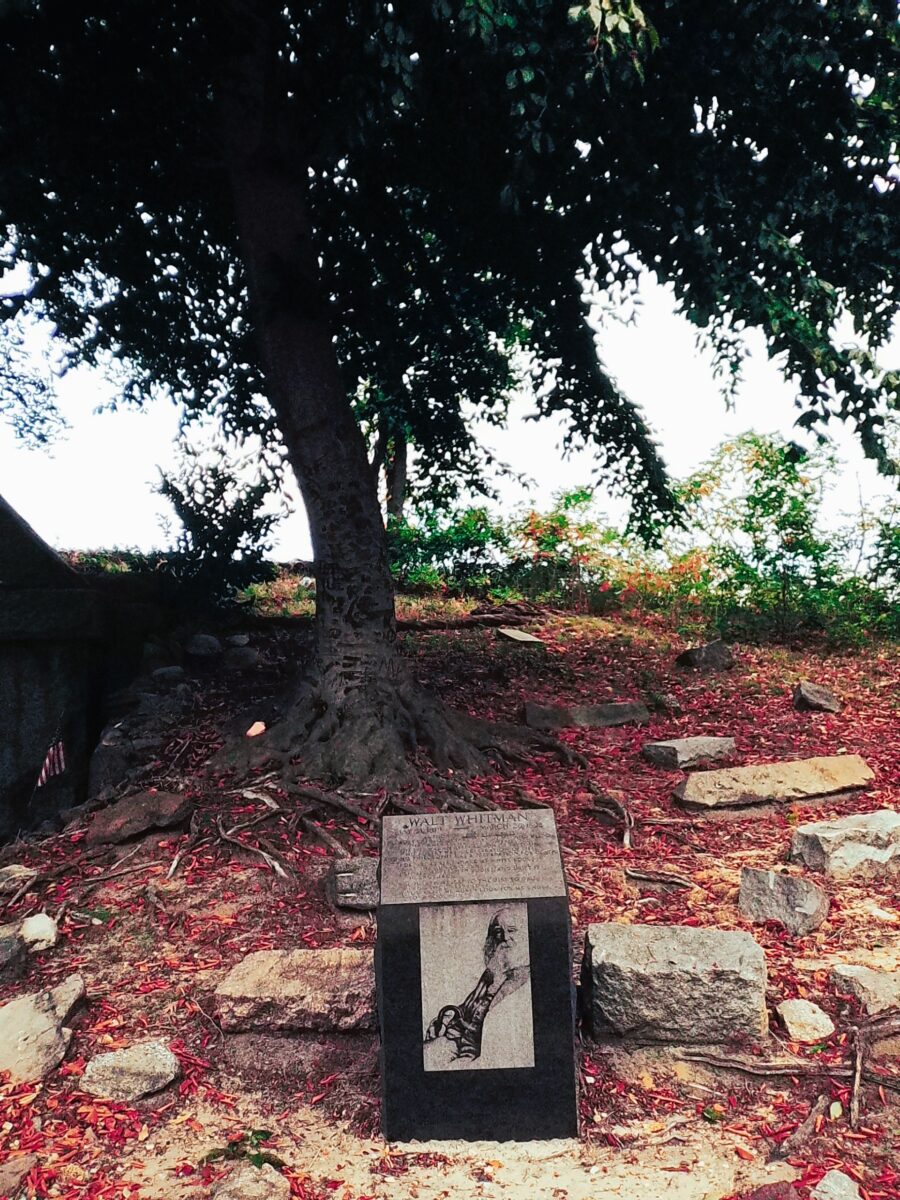

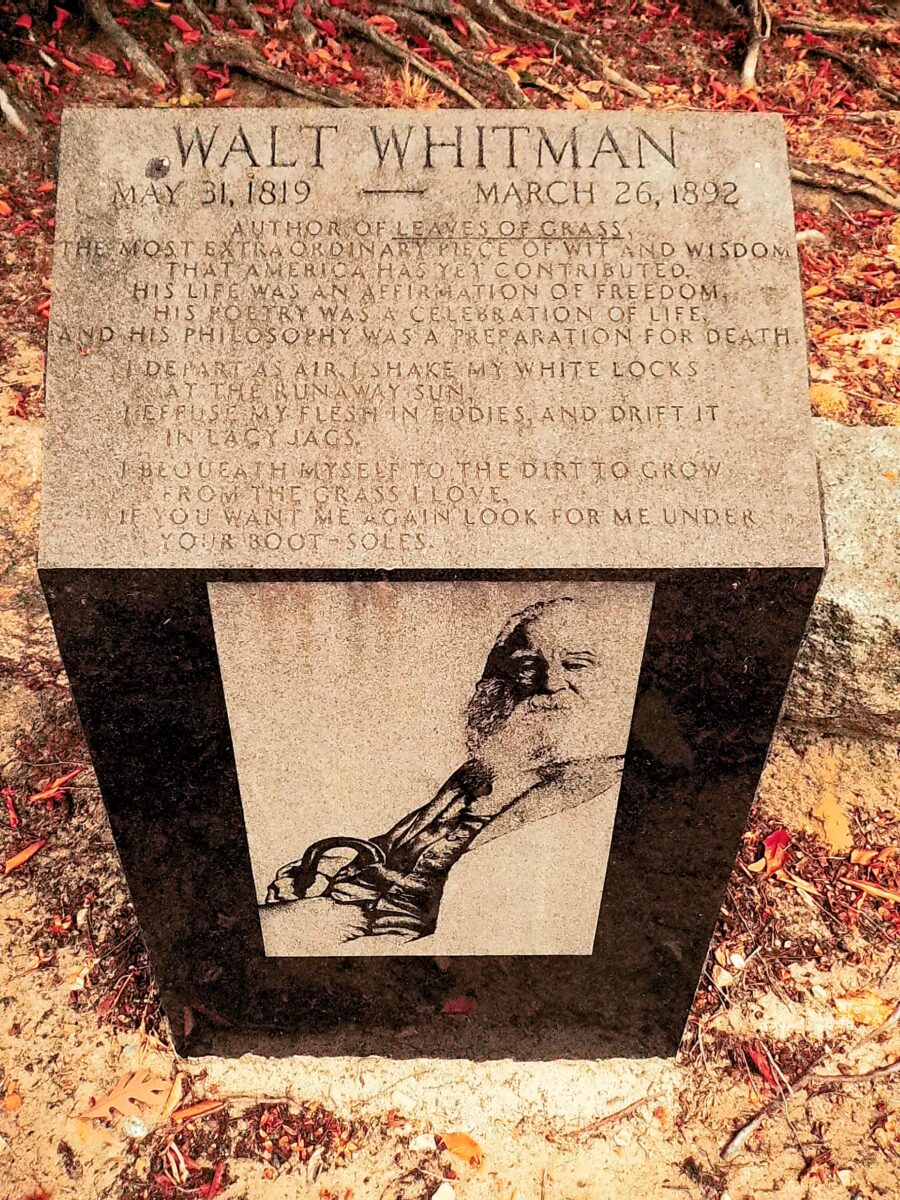

Walt Whitman very much wanted future generations to visit his final resting place at Harleigh Cemetery in Camden, NJ. He spent years and lots of money designing his own grave site.

Indeed, he was more interested in designing and financing his own grave than he was in any house he ever lived in – though to be fair, this is about constructing and preserving his own legacy, and not necessarily to evoke any creepy sensibility (NJ Park Service, 10/8/23).

And yet, walking around his carefully designed grave and memorial, Whitman’s poetry hits differently. It sure seems like death, his own as well as as the abstract concept, was on his mind and in all of his work:

“Something there is more immortal even than the stars,

(Many the burials, many the days and nights, passing away,)

Something that shall endure longer even than lustrous Jupiter

Longer than sun or any revolving satellite,

Or the radiant sisters the Pleiades.”(From “On the Beach at Night”)

“And as to you Life I reckon you are the leavings of many deaths,

(No doubt I have died myself ten thousand times before.)”(Section 49 of “Song of Myself”)

Nightmare Fuel: Walt Whitman’s Missing Brain

If you are in the mood for even more macabre imagery, consider the caper of Walt Whitman’s missing brain! In life the poet was interested in medicine, and the leading science of his day brought him to an unfortunate interest in the now-discredited field of phrenology. By the time of his death, however, Whitman had renounced phrenology and wrote letters to friends mocking its charting of bumps on a person’s head in order to discern their personality or innate traits.

Before his death, Whitman allegedly agreed (in words only, no signed documents were ever found) to donate his body for study at the Wistar Institute. Many of Whitman’s organs were removed for study and preservation, including his lungs and many tumors across his body (common in that era for someone who reached the age of 72) (NJ Park Service, 10/8/23). But unfortunately, after Whitman’s brain was removed, the specimen was damaged and went missing. Pathologist Henry Ware Cattell claimed publicly for the rest of his life that his assistant had dropped Whitman’s brain and rendered it unusable.

Only very recently has Cattell’s story been proven to be not entirely true. In a strange twist of fate, Cattall’s personal diaries sold over eBay to a private buyer in 2012. In these journals, Cattall berates himself for being the person to ruin the deceased poet’s brain. He apparently forgot to put the lid on the brain jar, so preservation failed and the organ decomposed.

But this fabrication of an assistant dropping and damaging a preserved brain haunted the American imagination and has left its fingerprints on art and pop culture: namely, the 1931 film adaptation of Frankenstein. This film version features a scene that did not exist in Mary Shelley’s book, where Dr. Frankenstein’s assistant drops a brain preserved in a jar labeled, “Normal Brain,” rendering it unusable. In the 1931 film, the monster must instead be given a brain that belonged in life to an executed murderer. This is an anachronism; in 1818 when Shelley wrote her masterpiece, the brain was not understood as the anatomical place where the mind lives. And besides, the technology to preserve brains in jars did not yet exist.

When Cattall told his lie about “his assistant” ruining a famous poet’s brain specimen, he couldn’t have known that his fib would take on a life of its own, and continue on in a scene of an enduring tale of human-caused horror.

To be fair, what happened to his remains after his own death are hardly Walt Whitman’s responsibility. As for Whitman, his life was brief in the grand scheme of things, as are our own, and he remembered this sad fate every lilac season.